Photography: Daniel Arthur

"I think songs should be hot and sweaty, like I am now."

So says Merrill Garbus, midway through the best gig I’ve seen this year. Yes! Songs should be hot and sweaty. Songs should stamp and dance like she is doing. They should breathe fevered and damp on your neck, pulse tangible waves through the air, ruffle your hair with whomps of sound and life. You've got to feel them. Merrill’s absolutely right. Maybe this is key to the tUnE-yArDs puzzle: a band that had me hooked from the first video I saw of them but somehow failed to bottle the genie on record. The songs needed to be hot and sweaty and alive, not plasticinated by some Gunther von Hagens of a record producer.

Maybe this is key to the tUnE-yArDs puzzle: a band that had me hooked from the first video I saw of them but somehow failed to bottle the genie on record. The songs needed to be hot and sweaty and alive, not plasticinated by some Gunther von Hagens of a record producer.

Maybe this is key to the tUnE-yArDs puzzle: a band that had me hooked from the first video I saw of them but somehow failed to bottle the genie on record. The songs needed to be hot and sweaty and alive, not plasticinated by some Gunther von Hagens of a record producer.

Maybe this is key to the tUnE-yArDs puzzle: a band that had me hooked from the first video I saw of them but somehow failed to bottle the genie on record. The songs needed to be hot and sweaty and alive, not plasticinated by some Gunther von Hagens of a record producer.So here's the video that won me over: it's filmed at an in-store gig; Merrill is cheery and peculiarly ordinary, as unflash as any toast-of-the-town musician I have ever seen. She’s wearing an awful patterned T-shirt with elephants on it and no make-up. I like her. She looks like the girl who prices up the soya milk in the health food shop. This is important. You wouldn’t catch the indie pop girly-girls with their dresses and tresses being so genuinely, unselfconsciously, gloriously plain. It makes her remarkable. Perhaps Merrill Garbus is the anti-Zooey Deschanel? I fucking hope so.

And there’s the way she scrunches up her nose and opens her big mouth wide as all get out, wide enough to swallow idiotic pop whole, The Vaccines and the Vampires and all the silly-shoed boys and hair-clipped girls, and shouts out loud. She knits her brows like a sulky toddler. Or a witch doctor. She whoops and twitters and hollers. At one point she stands and shakes her outstretched hands and growls, actually growls, for about a minute. Whoa. That got me.

As well as the look of the band, there’s the noise of it: two stand-up drummers; a battered ukulele; a jittery guitar; a pedal board. It sounds like nothing else. Which isn’t strictly true, of course: influences can be unpicked if they have to be, and zeitgeist-trailing fellow-travellers identified. I could say that she’s nicked the same percussive African guitar that Vampire Weekend have purloined; that she uses the abrasive close vocal harmonics and jagged rhythms deployed by Dirty Projectors; that I’ve seen exactly that sort of rackety bottles’n’cans percussion and awkwardness worn by Micachu and her Shapes and that Braids do a similar live-looping, multi-pedal-based, in-the-moment song construction thing. There are of course the cultural appropriations that so irk some commentators, not just the jit guits, but the polyphonic, polyrhythmic yelps and yodels of the forest-dwellers of Central Africa. But let’s go with the uniqueness.

Bloody hell, if I had overheard someone describing that band I’d have been salivating, given my long-term crush on shonky, DIY, defiantly unrock’n’roll female-fronted outfits (Pram, UT, fr’instance): I so want tUnE-yArDs to be spectacular. I so want them to ignite me.

There’re plenty of other tUnE-yArDs performances out there on video to give me hope: Merrill plays mix-and-match with band members and instruments – percussionists, brass sections, sometimes just her and her uke. There’s an obvious spark at play when she is conjuring up the music from the moment that doesn’t seem to catch on record. I loved – and agreed with – Brigitte Adair’s ace review of w h o k i l l : there’s certainly something both irritating and profoundly disappointing in the experience of listening to recorded tUnE-yArDs. Which is a shame, because Merrill Garbus has talked about the album as being shaped by playing live; being an explicit attempt to capture all that she learnt from touring her debut. If that was her intention, it has failed, although perhaps it was always a doomed endeavour, given the irreconcilable difference in nature between live and recorded versions of songs.

Usually the experience of seeing a band live is augmented by a more-or-less detailed knowledge of the music you’re hearing. You need to know what the song sounds like. Otherwise you’re missing a trick: you’re missing hearing the ghost of the recorded version buzz round your sweaty, excited, possibly drunk self with all its associations and memories. It’s a thrill-boost. A head-charged internal enhancement of your listening pleasure, Bose headphones for the soul. You know that song so well. You’ve listened to it dozens of times over in your bedroom, danced to it in the kitchen, you know every chord change and counter-melody: it’s yours. You fucking OWN it. Never mind that live the sound is dirty, that the PA is a dog, that they haven’t brought the cellist, the cheap bastards, that the bassist fluffs the chorus; it doesn’t matter because you can hear the song as it has already been laid down, you can hear the potential as tangibly as you can feel the bodies of the crowd around you. If you watch an unknown band playing unknown songs through shitty speakers, the music is really going to have its work cut out to catch your ear.

Coincidentally, and unfortunately for the band in question, tUnE-yArDs’ support, Thousands, were a perfect example of the flipside of this phenomenon. Two Americans with acoustic guitars, battling against the curiously cone-shaped venue which funnelled and amplified the sound of hipster chatter right onto the stage and into their faces, so that their delicate pickings were competing with several hundred ha-ha-ing haircuts. So they sounded like nothing. Like two blokes strumming. As dull as mud. Whereas, so I later discovered, on record they are all about the minutiae. Their songs breathe when studio-born, much more rarified beasts than the busked nonentities my ears heard that night. Their recording process is meticulous: they record outside, in specific rural locations, every gentle burr of the strings, every catch of the breath part of the poetry. It’s beautiful, through lush stereo speakers and in still air. It’s utter shite on a stupidly-placed stage in front of a distracted, bored, partisan crowd on a hot night in Brighton.

It doesn’t bode well for tUnE-yArDs. And this is the gig where I get to test my theory that the alchemy happens live. Huh.

I needn't have worried. It's perfect. The sound is clear and gorgeous, the performance miraculous. Blah blah blah. The thing is, with live music there’s nothing that can be done to convey the experience truly. Words fail me. Us. They leave gaps and create elisions, they trick and mislead. Shit. It’s not like writing about a song on the internet and embedding an MP3 so the reader can check that your whooping about its awesomeness isn’t just some hype-induced craziness. This is a doubly-mediated experience. And it’s not as if videos can really do it either, despite where we came in. Watching a video of a performance on a small screen is a qualitatively different experience to being in the venue, with all the roar and the stink and the friction.

I’ll try. Because it really does make a difference to what I heard that I was perched on the edge of the stage, my back against the speaker. That I could see the sweat dripping down the saxophonists’ faces, smearing the black streak painted across their cheeks. That I could feel the thump of the bass in my belly. That my legs got pins and needles but that I didn’t care; I didn’t want it to end. That the sensation of being a mere metre away from where two saxes were playing notes a microtone apart could be felt in my knees. Does it help that I found out that that sound is the ringing clink of a beer bottle being struck by a drumstick or that one is the particular clatter that a baking tray makes when thwacked by a joyous brass player? Does it increase my appreciation of the songs to twig that the reason Garbus doesn’t wear shoes on stage is because she uses a stripy-socked foot to twiddle a delay pedal and adjust the length of the loop (whilst simultaneously singing and playing the drums and the ukele)?

Yes. It does.

She is an accomplished, electric, performer. She stands out front like a tribal queen, an arc of drums and pedals arrayed before her, and builds her songs afresh each time. She writes and constructs her music in front of us, starting with a rhythm clicked out on the rim of her drum which is looped and repeated and manipulated and added to, vocalisations used as percussive rather than melodic elements, parps of brass and skipping lines of guitar looped and woven into the mesh in their turn, until there is an utterly thrilling web of noise pulsating on the stage. It’s a pretty remarkable thing to witness. It gets the place bouncing; at one point Merrill and her band and the whole crowd hop up and down in sheer synchronised delight like Masai warriors. She makes the crowd sing out a simple repeated phrase; she builds us into it all as if we were another instrument. She works the communal thrum until every being in the place is buzzed-up with shared joy. No time for irritation, no space for getting tired of the yodelly schtick: it's all about the heartbeat.

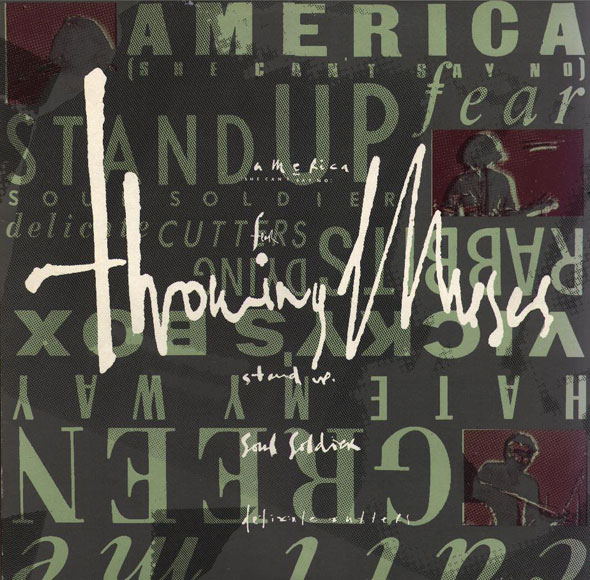

Cleverness is definitely a turn-on. Lack of botheredness about seeming cool is too. Being a savvy female musician, who clearly knows exactly what she is doing, who is deeply, geekily, competent and in control of the sound she is making, a conductor of and for magic: that totally rocks. Merrill Garbus shares this, and a kind of particular weird ordinariness, with Kristin Hersh (and, incidentally, with the pedal-head women in Braids, who look like wide-eyed junior English teachers and play like goddesses); unglitzy to the bone but deeply extraordinary – because this isn’t how pop stars are meant to be. They shouldn’t look or act or sing like this. They shouldn’t be this untrammelled, this peculiar! Where’s the rock? Where’s the roll? - and thus are quite the most intense performers imaginable.

So tUnE-yArDs do the bizness. I win. Maybe one day they will come close to the impossible goal of pinning down a moment in recorded form but for now THESE are the ur-version of the songs. THESE are their platonic ideal. No need for foreknowledge when the music comes to life in your gut, no need for ghosts when things are this alive. This is moment-by-moment ineffable specificity: there’ll never be this again. This is unique. This is now. This is here. This is mine.

And next time I listen to w h o k i l l, I'll also be hearing the whoops of that night, the memory of her socks and her audience and her grin boosting the digital signal and turning up the colours to full saturation.

(Originally posted on Collapse Board)