Six-year-old Kristin Hersh, in the way of small children told not to touch something because it’s not a toy, imbued the guitar belonging to her university professor dad (whom everyone called Dude) with mysterious and magical powers. She used to creep up and gaze at it longingly, imagining the thrilling sounds it would make when played.

Eventually Dude teaches her tiny hands to make E/G/A around the guitar’s huge neck but little Kristin is bitterly disappointed: the chords are boring.

“But Bob Dylan plays these chords. And Neil Young.”

“Mm-hm.” I looked at my hands, willing them to play better. “They’re probably nice guys.” Handing the guitar back to Dude, I stare at it, perplexed. Why doesn’t it sound as cool as it looks?

I complained that the chords didn’t sound magenta enough. “ … You know?”

“No”, answered Dude, bewildered.

“Well, red, I mean. I’ve heard red before. A million times. That chord was red. And boring.”

“E major’s red?” he asked. “E never sounded particularly red to me. You mean it’s a primary color?”

“Yeah. We didn’t even play green.”

“What chord is green?”

I shook my head and glared impatiently at Dude. “Mix a blue chord with a yellow one. Duh-uh. It’s stronger and prettier that way. Like those fish.” The fish I meant were African cichlids, who change color when they lose too many fights. They get their asses kicked enough times and grow pale, while the winning fish develop bright colourful scales and beautiful patterns … “If you play too many wimpy chords, you’re just asking for wimpy scales.”

“Are you calling Bob Dylan a loser?”

“No, just a pale fish.”

Dude looked at me sideways. “Are you calling my scales wimpy?” I shrugged and he handed me the guitar. “It’s yours,” he said. “Play colors”.

*

And so she did. The songs Kristin Hersh wrote with her band Throwing Muses are kinaesthetic wonders, flashing bright with fire and fury. Her autobiography, Paradoxical Undressing (Rat Girl in America), covers the frenetic year in which the 19-year-old Hersh is hospitalised with manic depression (“They don’t call it that anymore”), signs to British label 4AD, gets pregnant and along the way writes some of the most extraordinarily affecting, astonishing and inventive pop songs that have ever been recorded.

It does make me wonder how people who’ve never heard Throwing Muses experience this book. (Fuck knows what they imagine the band sounds like but I’d love to hear the music a forensically-minded reader might make, reconstructing Throwing Muses solely from what Hersh has written. It'd be awesome.) But if you do know their self-titled first album from 1986, the Chains Changed EP (1987), second album House Tornado (1988) or the In A Doghouse cassette of demos from 1985 (released on CD in 1998), then you can be sure of a hundred little epiphanies and the mental clicks of puzzle pieces fitting together. The narrative colours-in the recollection of familiar songs, and imagery that might have struck one as purely cerebral is revealed as having its feet set in concrete reality; not altogether an expected situation, given that Hersh has always been so clear that her songs drop from the ether, in a process not so much of being written as transcribed.

So the lyrics of ‘Fish’ (from In A Doghouse; also on the 4AD Lonely Is An Eyesore compilation (1987) : "I have a fish nailed/To a cross/On my apartment wall/It sings to me with glassy eyes/And quotes from Kafka") are revealed to be about an actual scaly crucifix on the wall of the squat the teenage Kristin sometimes sleeps in, rather than hallucinogenic word play. (The story about 'Hate My Way' is far too good to quote now: you’ll just have to find it for yourself.) This demystification manages to be simultaneously delightful, satisfying and alarming, not least because the hallucinations, when they do appear, are all too real: Jesus Christ, she slept alone in a haunted apartment under a fishy, donut-headed Fish Jesus? Oh, little homeless Kristin...

Alongside the pleasurable ‘Oh!’s of recognition you get when spotting the genesis of well-loved songs, Hersh has left snatches of lyrics scattered throughout the text, which widen the book out into an extra, noisier dimension, so that cached songs burst out from memory-banks at appropriate moments, a self-generated soundtrack. It’s lovely. Startling. Discomforting. So, after describing the dressing-up wigs that the band, all sleepy and snuggled up against each other in the front seat of Kristin’s unheated car, take to wearing on the way back from late-night gigs (both to keep their heads warm and to provoke non-boring conversation), she drops a lyric from ‘Carnival Wig’ (from Red Heaven, 1992), into the mix and suddenly there it is, a riot of crashing percussion broken up with that sinuous, heartbreaking guitar line. The disconnect between the image of tired kids in their funny wigs and the triggered memory of the song itself is positively unnerving: her voice all jagged on the urgent one-note central line ("That looks like a carnival wig/And two shiners") then sliding into raw sexual desperation: "It looks like your left hand/Don’t love me. Don’t love me." The kookiness wiped out in an instant.

The sound in one’s head that accompanies the reading of the book, along with the startlingly vivid images that Hersh employs (New song is done. It’s burgundy and ochre with a sort of Day-Glo turquoise bridge – another tattoo on this pathetic little body) and regular vignettes of life from her hippy childhood (Allen Ginsberg wrote me a poem … it wasn’t a very good poem) foster an entirely appropriate sense of overload, given her own of experience of the world as a constant assault of sensation, colour, sound, emotion.

She’s an innocent abroad, candid to a fault, observing the world and its peculiarities with wide-open eyes: sometimes sitting out, sometimes indulging people’s demands of her to go along with rituals she barely gets the point of, sometimes consciously (though not contrarily) sticking to her own eccentric ways in order to survive. So she won’t wear her contact lenses when they play gigs, despite being nagged to do so, and she won’t wear a coat in winter:

Dave and I always believed that coats were for wimps who couldn’t handle seasons: “coat slaves”. Gee, people, get a grip! Seasons happen! And that vision was for wussies: people who couldn’t hack the rough-hewn, fuzzy life we lived – slaves to their glasses – when we could play entire shows without seeing anything. It was the only thing we were smug about, really, our ability to live blind and cold.

At least until Dave (Narcizo, the drummer) finally caves in himself and then drags her off shopping to a thrift store and buys her a small, blue, woollen overcoat: Dave unzips his coat to show me how it works. “See? We can still wear our T-shirts, but if we wear out T-shirts underneath coats, winter won’t hurt!”

She and Dave also puzzle over other people beyond their Musey bubble, like “the aliens” in their shared house, and grill them about the ‘normal’ music they play, incredulous that there are people in the world who put their feet up on the table while they play guitar, don’t get hot or feel electricity when they make music, who strum strings to relax: they might as well be sitting there doodling. While passages like these occasionally teeter on the verge of disingenuousness, overall the impression is of genuine teenage insularity rather than retrospective faux-cutseyness.

Her innocence, curiosity and wit are surely not only what makes her writing so appealing, so fresh, but also the reason why Kristin Hersh has a reputation as one of the very nicest musicians to work with. She’s both interesting and interested. Not that common a trait in the biz. And it’s obvious how very fond the band are of each other, not just Kristin and Tanya Donelly (‘Tea’, her step-sister with whom she started the band at the age of 14), but also Leslie Langston, the dreadlocked hippy chick Californian bassist and Dave, the afore-mentioned snare-prodigy. They are entangled in the joy and awe of playing together, rehearsing in the attic of a giant Victorian house that belongs to Dave’s parents (who sit in comfy chairs at the bottom of the stairs and listen to the band practise), playing gigs several times a week, and eventually all moving in together, away from the ocean and the small-town comforts of Rhode Island, to a shared apartment in Boston.

When I first started reading about Throwing Muses back in 1988 I was concerned, as was my earnest wont back then, that Hersh’s frankness about the unusual way she ‘wrote’ her songs would have her pegged as just another crazy woman, reducing the extraordinarily muscular inventiveness of her music to mere kookiness; such an easy, diminishing, write-off for the boy journos. What I wanted was to celebrate the unconventional accomplishment of her music, to group her talent in a girl’s gang of underappreciated musicianship, with the likes of Kate Bush and Joni Mitchell. You can’t very well do that with music if its author refuses to credit herself with its creation.

If you haven’t already come across Hersh talking about the way her music comes to her, then the passages in which she describes the process will be enlightening. She calls herself “a lightning rod for songs”: not a songwriter, not an inventor, but some kind of psychic secretary uncomfortably possessed by music which is an entirely separate entity to herself. She writes of being haunted by songs, battered and tormented and bullied until she can get them down and safe. It’s not craft, it’s alchemy. The story of this strange phenomenon begins when she is knocked off her bike by a car and badly hurt. She hears her first song recovering in hospital:

Soon, the song began organizing itself into discernable parts that sounded less like “machines”. Instruments played melodies rather than disembodied tones in the bed of ocean waves: bass, guitar, piano, cello. Punctuated clanging became drums and percussion. I guessed that my brain was making sense of something, turning this sonic haunting into vocabulary with which I was familiar.

… every few weeks, song noise will begin again, and when its parts have arranged themselves, I’ll copy them down and teach them to the band, making them hear what I hear. As soon as I give the song a body in the real world, it stops playing and I breathe a sigh of relief, in precious silence …

… It’s not me. A song lives across time as an overarching impression of sensory input, seeing it all happening at once, racing through stories like a fearless kid on a bicycle, narrating his own skin.

(How good is that phrase, “racing through stories like a fearless kid on a bicycle, narrating his own skin”?)

One of the great things about reading Paradoxical Undressing is that I can finally lay my qualms about the ineffability of that process aside, daft as they were anyway. The skill is there all right. They were an immensely clever lot, those Muses kids, and worked phenomenally hard to get their music right; they deserve every bit of credit they get:

Leslie never misses a beat. Never. Dave never misses a beat either; he smashes delicately, the deep sound of his kit punctuated by the metallic knocking of cowbells, mixing bowls, hubcaps and busted tambourines. It’s beautiful. But Dave never messes up because he can’t be distracted. He’s just as nearsighted as I am and lost in his own world back there behind the drum kit. If he looks up, it’s like a mole digging his way up from the underground, squinting in the sunlight.

They rehearse and play and rehearse and play, Kristin’s years of classical guitar training and child-genius Dave’s precocious talent aiding the songs’ troublesome journey from insistent disembodied furies to definite pieces of music, although even then Hersh is self-deprecating about her part in it and the otherness of the song’s own voice:

I can start a song just sorta, you know, singing along, and then, before I know it, inflatable words fill my rib cage, move into my mouth. I gag on them and they fly out, say whatever they want, yell and scream themselves.

And bleech, that voice – it’s wretched. My speaking voice is low, husky and quiet. The song’s voice is loud, strangled and wailing: thin and screechy. A squashed bug might sing like this.

Going away is my only talent.

I wouldn’t say so. Not least because she is such a fine writer of narrative, which surely she can rightfully claim as all her own work, as much as any writer can. It’s such an engaging story, this year in song of hers. She’s a baby-faced urchin in old woman’s clothes, running from place to place, hardly sleeping, swimming to burn off energy (I’ve never tried to make it through a whole day without swimming. Water temporarily washes off song tattoos, so I made it my drug), sleeping in abandoned apartments and in her unreliable car and on the beach. She goes to classes at the university where her father teaches (she enrolled at 15) and where she meets her friend, a very elderly Betty Hutton (in her time a great Hollywood movie star, although Kristin, in her naïveté, doesn’t know whether to treat Betty’s stories of tête-a-têtes with Judy Garland as yet more fantastic eccentricity). I love the idea of Betty and her priest, Father McGuire, coming along faithfully to every Throwing Muses show, standing at the back behind the junkies and the painters and the punks, smiling fondly and giving Kristin advice about the big time show business career Betty feels sure is round the corner.

And so it is, in a way. Hot-shot A&R men wine and dine them, the teenagers revelling in all the free food but puzzled by the attention, because they truly don’t understand why anyone else would like the noise they make. And they won’t sign to any one of those labels because they know they’re not cool and they don’t want to play the game.

But when Kristin’s bi-polar disorder kicks in hard and she starts to come apart, the reading gets more painful. The narrative falls into little fractured bits: more snippets of lyrics, less coherence, horrifying descriptions of Kristin’s tortured thoughts and hallucinations, disintegration. It’s disjointed and almost unbearably sad to read:

Music’s making me do things, live stories so I can write them into songs. It pushes my brain and my days around. A parasite that kills its host, it doesn’t give shit about what happens to a little rat girl as long as it gets some song bodies out of it. It’s a hungry ghost, desperate for physicality.

I remember well the strange little person she appeared to me in 1988, a couple of years after this book is set and a couple of years older than I. She was wearing an A-line khaki skirt and a neat blouse and I remember thinking “Why on earth would you wear that to a gig?” Especially in a dirty, glassy, glitter-balled punk rock club in Birmingham, on tour with inkie-darlings and fellow Bostonians, Pixies. Inexplicably, she looked like the me I was trying so hard not to be: dark blonde hair cut in a wavy bob; round, childish face; sensible outfits … but transmogrified when she played into something mesmerising. A she-wolf. A snake. She was like no one I’d ever seen before, playing music that seemed beamed from an alternate universe, tethered to recognisable shapes of pop and rock by only the most tenuous of lines.

“Well, geez, look at me,” I said, pointing at the screen. “I really don’t blink.” We watch. “Golly, that’s creepy.” I knew I stared into space when I played; Betty never stopped giving me shit about that. She should have been giving me shit about the thing I do with my head. It swivels from side to side in a figure-eight pattern while I play. What the fuck? “I think of it as an infinity symbol,” said Dave kindly.

Tremendous, she was. Those songs snagged at me, painful and demanding, Kristin’s squashed bug voice the perfect vocalisation of all the jumble of emotions my teenage self was experiencing, the switchback ride they took - roaring through cowpunk frenzy via dischord and ecstasy to sweetness and charm - an apt representation of where my head was at, where haywire teenage heads tend to be at. And those words that I could barely grasp at understanding but which made total sense to me, all blood and rage and impotence and self-loathing, here they are again, sewn through the story of a real girl

So I have to acknowledge that the sadness that lurched in my gut when reading my way through that bit of the story is much about the strange little person I was in 1988 as the extraordinary/ordinary girl I was watching on stage. The feelings that Throwing Muses provoked in me then came roaring back at me full-throttle with the account of Kristin’s breakdown and I ended up reading through tear-bleared eyes, surely a measure of just what a remarkably eloquent writer (ahem, conduit) Hersh is, both of songs and of stories. Because of the way that so many of her songs rage and fume, gurgle with ugly (self)hatred then liquefy into beauty and tenderness, hold themselves on achingly lovely melodies, then turn on a penny and then come crashing back into chaos and mania, even those of us who didn’t have hotwires to genius in our heads, who haven’t lived the awful/amazing/brave life that Kristin did as a teenager, even bog-standard youth, can hear those things and say, yes, that is what it feels like to be young and confused. Nothing ever spoke to me of being a nineteen year-old-girl, torn between being good and being furious, between romance and horror, between sensible shoes and razor blades, quite like Kristin Hersh’s remarkable, terrifying, goddamn gorgeous rollercoaster voice.

There’s so much else here to relish besides: the off-beat small-hours trans-Atlantic phone conversations between Kristin and 4AD's Ivo Watts-Russell; the wonderfully astute descriptions of the recording process (rats running round the night-time studio when they record their demos; the agonising multiple attempts to re-capture the manic verve of their live performance when recording their debut for 4AD); the snort-inducing interviews with well-meaning but dim journalists who ask endless variations of the ‘why did you decide to be girls?’ question (“Why didn’t you hire a woman to play the drums?” she asks me accusingly. I’m at a loss. “Because Dave’s not a woman,” I answer. “I didn’t hire him anyway; he doesn’t get paid.” “I’m a volunteer!” Dave chirps happily) and of course, the sweetly-written course of Kristin’s pregnancy, culminating in the birth of her first son, marking the beginning of her career as working musician and mother, someone who puts her babies to sleep then walks on stage to scream and holler; who is articulate and charming on TV interviews while being infinitely patient with the sleepy toddler on her lap. She’s amazing.

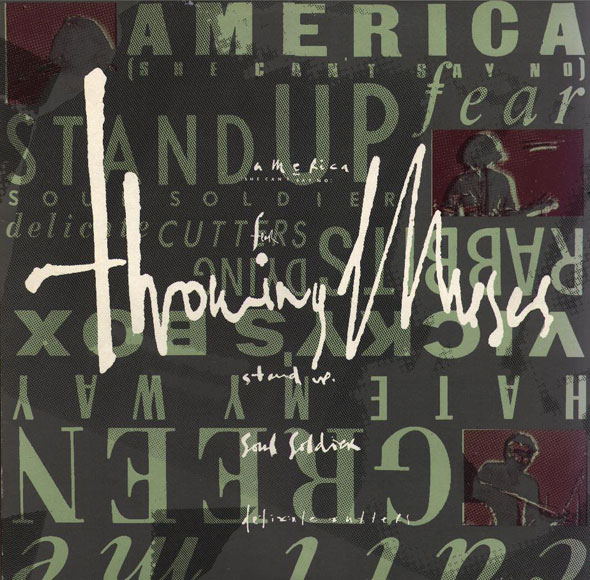

But really you just need to read the book. And if it doesn’t make you run back to ‘Call Me’ and ‘Soul Soldier’ and ‘Rabbits Dying’ and ‘Vicky’s Box’ (yes, there’s a Vicky. She has a box. A wooden box.) and ‘Delicate Cutters’ (oh, my god, ‘Delicate Cutters’!) just as fast as your ears can take you, then nothing else will.

I made the other Muses hear what I heard. Now we can make everyone else hear it.

(First published on Collapse Board)